- Home

- Stacey Mac

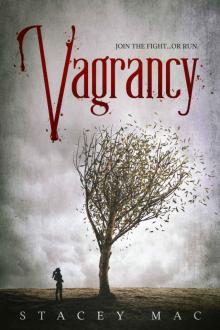

Vagrancy

Vagrancy Read online

Vagrancy

Join the fight...or run.

Stacey Mac

Contents

Title Page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Author’s Note

Chapter One

I roll onto my back, look skyward, and see no sky.

I don’t know the last time anyone has. Instead I stare into smog, shrouding us, blanketing what is left of the planet with its putrid cloud.

Irreparable.

For future reference, that smog is a metaphor for our fucked civility.

Annoyed, I heave myself into a sitting position, brushing dead grass to the dead ground. I should be using this free time to do something cheerier than sitting and sulking about smog and existentialism; but as a human, it is selfishly satisfying to complain about the world and how you cannot change it.

I suppose it is a nice day, as far as days go. The freezing wind has disappeared for now and the sun is fighting quite admirably through the smog to warm the earth. I am still cold, of course. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t cold. But with the faint yellow glow pushing through, I can almost imagine what life would have been like if lived in the sun.

The clearing is protected by a forest border: a rarity. As a general rule, large areas of any kind of flora do not exist anymore, unless they had been planted for harvesting. This forest, however, has not been cut down in my eighteen-year lifespan. I should know; the farm I live on is bordered by these woods.

I sigh and move away from the miracle trees. My mother and father will be wondering where I am.

I wander slowly back to my family’s fields, my eyes on my leather boots, contemplating what left there is to do before I can collapse; muck out the shed, feed the goats, collect our ration of water for the coming week.

I am distracted in my counting, not noticing the hand that swings out towards me.

There is a sound of skin striking skin, and my head jerks violently. I fall sideways, landing in the dirt with a huff as all the wind in my chest flies out. My cheek stings. From here on the ground I can smell the rawhide of his boots, and I react quickly. I scramble to my feet, standing ramrod straight at attention, breathing like a weasel.

Commander Snare narrows his eyes, his mouth curves into an ugly smile. Commander Snare’s face has thousands of lines. Each crease weaves its way to his mouth, a map of streams leading to a sinkhole. I can’t remember a time when he didn’t smile happily.

If you haven’t pieced these two things together yet: his bigotry and his happiness at being a bigot, than I should explain that he is also an asshole, and our leader. And really, what leader isn’t?

Although his mouth is unchanging, his pale, colourless eyes are almost always expressive. His grey brows are constantly in flux so that one moment, he is kindly concerned and the next he’s happily murderous.

He speaks sweetly. “Our sector is depending on you, and here you are, strolling back from a daytrip in the woods?” His head is tilted to the side.

I’m not a badass, I just have badass thoughts; so fear streaks through me when he says this. I stand unflinching and give no reply. I’m not permitted to reply. I’m never permitted to reply unless I’m asked a direct question, which this is not. His words sound mild, but I hear the threat behind them. Commander Snare can be enraged and calm all at once. He’s just that clever.

Of course, I’d broken no rules. I am not allowed to enter the woods, and so I hadn’t. I am sure he had seen me sitting more than fifty feet from the boundary line, as well, and knew that I hadn’t ignored orders, but the honourable Commander of our sector never misses an opportunity to display his dominance to the young, the weak, and the female.

I am all three.

His colourless eyes pierce mine. “Were you trying to reach the other side? Perhaps your duties here do not satisfy you? You know, crossing the boundary without permission is considered high treason,” he says conversationally.

Years of experience has taught me to be still, silent, and accepting of whatever comes to me. Accept, endure, and obey: this is the creed our sector lives by. So I swallow bile, tremble delicately, and wish I wasn’t such a coward.

Mercifully, a man approaches the Commander and I cautiously.

“Commander Snare, is there some way I can help you?” My father – middle aged and covered from head to toe in grime – calls out from behind Snare. He holds his hands in front of him, a gesture of peace, but his eyes shoot furtively to mine, again and again, warning me to shut up. My very own personal Calvary.

“Stuart!” Snare cries with false delight, “There you are. I was just illustrating to your daughter the importance of watching the boundary line. People may get the wrong idea about your family if they see her blatantly breaking rules.”

My father smiles back, but it doesn’t reach his eyes. “I’m sure she didn’t mean any harm, did you, Tess?”

I shake my head stiffly, and as I do so, my father nods carefully behind Snare’s back, discreetly approving my silence.

We both know that talking will earn me another slap.

“Perhaps she’ll learn some discipline that you couldn’t impart on her at the training compound. I’d hate for her to bring down punishments on your whole family,” says Snare. His ridiculous eyebrows dart in and out: wondering one second, brutal the next.

“Is there something I can do for you?” My father asks again, diverting the attention from me. I relax slightly as Snare turns his back on me.

“Just a small matter, Stuart. I noticed your contribution last week was late. I wanted to impress upon you just how important your work is to our sector. Surely it won’t happen again this week?”

The Commander is talking about our family’s duty to provide food rations to our sector. As grazers, we are one of several families in charge of farming and harvesting food. The wheat, goat’s milk and various animals that we hold in our fields are to be delivered to Council by dusk, every Friday, every week, no exceptions. It doesn’t matter that it hasn’t rained in over two months. No one cares that we are trying to grow crops in dust. There are many mouths to feed here, and the food our unit provides has to be rationed and distributed to the people of our sector: Galore.

“My apologies, again, Commander,” my father says cheerfully. “And of course I’ll do everything I can to get our contribution to council on time. We are still hoping for rain this week, and that should make our load easier for the coming months.”

To clarify, by ‘late’, we are talking about a few hours.

I don’t know how my father manages this charade, week after week – the pretence that he respects Galore’s leader, and that he appreciates his role here. He is a career liar. Only someone who knows my father well can see the strain. The vein in his neck, tensed and pulsing, tells me just how much he’d like to beat the shit out of this man.

>

I would thank god for his restraint if there was one (but I’m pretty confident our world was either godless from the beginning, or He wrote us off as a failed experiment and abandoned ship). I am terrified of losing my father, and I don’t know what my mother and I would do if he was taken away and imprisoned, or shot. I am far too experienced to know how little it would take for Snare to do just that.

“Glad to hear it,” Snare says, “I’ll let you get back to work, then. There are still a few hours left in the day, after all.” With one more derisive glance back at me, he strides off across our fields and back to the car that is waiting for him in front of our house.

It isn’t until it is out of sight, leaving clouds of dust behind it, that my father and I let out deep sighs.

Dad walks to me immediately, placing his hands lightly on my shoulders. “You okay?” He asks. The politeness is gone, replaced by his normal speech and tone.

“I’m fine.”

He brushes his fingers across the mark that must be rising along my cheekbone. It stings under his touch. “What were you doing? Trying to get yourself shot? I tell you to take a break, and the next thing I know, you’re being backhanded by the Commander.”

“What’s new?” I ask. “And I wasn’t doing anything, I wasn’t even close to the border, really. I was just lying down over there.” I nod to the clearing over my shoulder.

He groans, releasing me and beginning the short walk back to our house. I follow him, touching my cheek gingerly.

My father is wearing gum boots with his uniform trousers tucked into them. They are the same khaki pants that the Galore soldiers wear into combat. My father looks much like me, with the same light brown hair, only his is cut so short I can see his scalp. His broad shoulders are the product of the years he has spent farming our fields, and the lines on his stern, tanned face reveal just how much it has weathered him. Whenever he is the bitter old man he sometimes appears, I remind myself it hadn’t always been so.

Before I was born, my mother and father had met and married in a city known then as Toronto. Now, Toronto is a wasteland. It is the same almost everywhere. War broke when our world leaders began breaking alliances after Earth’s natural resources - like oil and coal - were declared scarce. When the United Nations disbanded, it triggered a series of nuclear attacks. The bombs obliterated entire cities all over the world. Peace was lost, first between common enemies, and then between previously allied countries. Finally, the virus of war spread within the remaining nations. When habitable land and food became difficult to come by, sovereign states began to turn on one another, forming militias to protect what little their population had left, or to acquire what they lacked. Over the last quarter of a century, the fight has continued, but instead of the bedlam and skirmishing, it has become more organised. Those that are left in North America belong to one of many militias that we call sectors.

Our sector: Galore, was established to protect some of the only fertile land that can be found for hundreds of miles in any direction. Galore is vast and populated by only four thousand of us, but we have managed to hold this abundant part of the continent for the entirety of the war. Many will brag that this is because we are smarter, more ordered and obedient. If you ask my father, this isn’t the case.

Our sector is divided into units, so that everyone is clear of their role in protecting what we have in Galore.

My mother, father and I, are called grazers, our unit organises, grows and harvests what we can to provide food to every mouth in Galore. Our duties are commonly thought of as the easiest, saved for the weakest of our sector.

The command unit is by far the smallest, and comprises of administrators, and at its head – Commander Snare. We call this unit, Council.

Frontline soldiers are our first response unit. They are our most skilled fighters, tasked with watching the boundaries for oncoming threats. ‘Fronters’ are the most respected members of our sector, after Council.

The medical unit is exactly what it sounds like; they are our doctors and nurses. We call them medics.

Trainers are our most highly ranked frontline soldiers. They are in charge of coordinating our militia, strategising, espionage, and training our children for combat.

Because everyone must fight. We give each other titles and divide into roles, but we are all just soldiers, biding our time.

Every single one of us. Me, too.

It is the same everywhere. Every militia is comprised of nothing but fighters, willing or not. They take us from our homes every year, and they carve us into killers. They attempt to make us the strongest, the biggest – because in the end, the militia left standing won’t be the ones who can grow the best wheat.

For a quarter of a century, this is all there has been.

So we all live, we fight, and we die trying to survive.

No one knows what the world’s population has been reduced to, since communication between militias now consists only of letters carried by messengers. We can only estimate that we are a small percentage of tens of thousands, in a world that had once held over seven billion, all living mostly in peace. That’s funny in a way, because the thing is, now with so little of us left, one could imagine that there is enough fertile land. There is enough food and water for all the sectors, at least in this part of the world. Mankind may have obliterated a staggering portion of the planet, but a more crippling percentage of mankind was obliterated with it, and that number continues to plummet.

Surrender? Resist? It is not an option. Even though we risk extinction, and though we have the opportunity to rebuild, too much has passed. We fight now to settle vendettas. That’s what we live and die for– bad blood and revenge.

That is why my father looks years older than he should. Because we are contributing to a fight he doesn’t believe in, a fight that will never end. Accept, endure, obey – or die. That’s the choice. And so we contribute. We pledge allegiance to Galore.

“Want to help your mother with supper?” Dad asks me then.

This is an offering. I still have chores left to finish; the sun will still be up for another couple of hours, somewhere above the smog. But there is only two days left before this year’s training begins, and then I will be taken away from my parents for twelve weeks. I know how much my father hates that I will have to go. This is his way of compensating.

“I have to feed the goats,” I say with a smile.

“What am I, chopped liver?”

“At least let me go get our water, otherwise we’ll be eating raw tonight,” I say, chuckling under my breath. If my mother and I would let him, my father would do all the work himself. “If you want, I can spend tomorrow lying around in bed while you and Mum serve me food.”

“In your dreams,” he says, although he is still looking sad. He sighs then, “What time are you being collected on Monday?”

“Dawn.” On Monday morning there will be a van that will come by our house with two armed soldiers. They will be making sure I get safely from my home to the training compound, along with all the other initiates in the immediate area.

My father shakes his head, and I know what he is going to say next.

“This wasn’t the life I planned on.”

He has said it a million times. He will live out the rest of his life wishing for something more and hating himself for never finding it for us. That world he wants was burned down a long time ago.

“Go on, then,” he says. “I’ll see you at supper.”

Chapter Two

The command unit is situated in the heart of Galore.

It was once a courthouse, a place where criminals were put on trial so that the leaders of the free world could decide if they would be imprisoned. That’s the rumour. I suppose not a lot has changed then, except I’m fairly certain that in its’ prime, this building had not had half of its pillars obliterated to tooth picks and canyons carved out of the vast steps that lead to the entrance.

On Mondays, the entire sector meets here

to receive news of our militia’s proceedings in the war, on Wednesdays we meet to collect one week’s ration of water per household for the non-grazers, and on Fridays; food rations. Today, the water barrels are set out along the bottom steps of Council. People are swarming around them, grabbing their fair share before walking brusquely away with their carts or wagons. No one stops to talk, and no one takes more than their families’ ration. The armed frontline soldiers standing every ten feet or so along the steps are checking our identifications, ensuring no one becomes too brave, or too stupid.

Our Unit Identification Codes (UIC’s) are six character sequences that identify our unit, and our number within that unit. The aluminium UIC tags have to be carried on one’s person at all times. Mine is hanging around my neck, tucked under my shirt. It says: G00136. I am the one-hundred and thirty-sixth of the Grazer unit.

Once, I had a surname. We all had. Council had found this hard to keep track of. An army could conduct itself better with codes. Codes have order and secrecy. For the last ten years, my name has been Contessa G00136, daughter of Stuart G00038, and Anne G00039.

I pull out my UIC tag and hold it out for a fronter to look at briefly. The soldier nods, gesturing to three barrels. I heave these onto my wagon, grunting as I do so. The fronter snickers, obviously enjoying my weakness.

It is like a warm up. In two days’ time, every person between the ages of ten and eighteen in Galore can enjoy my demonstrations of weakness in the training centre. I have little-to-no upper-body strength. Paraplegics and people with no legs left still have upper-body strength, and the upper-hand. I have the upper of nothing.

The walk home takes around an hour and passes the other grazer households. By households, I mean the simple rectangular structures that look more like concrete igloos than anything else. Almost every member of Galore lives in one of these boring shelters, unless you are a part of Council, or living at the training centre.

The escalation of the world’s war happened before I was born. My father has retold me everything he knows about it, about why we are here. War is sparked with fear, fear of each other, fear of losing control. It is fuelled with greed, though. The greed took electricity, running water, technological advance, oceans of blood. Greed takes everything.

Vagrancy

Vagrancy